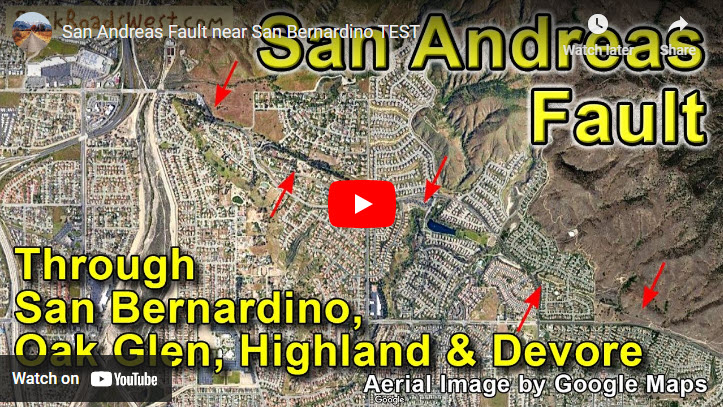

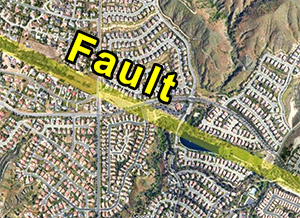

San Andreas Fault in San Bernardino

Along with our other road trips along California’s San Andreas Fault, this tour takes us through the streets of San Bernardino, Highland, Yucaipa and Oak Glen, which are all cities within the region known as the Inland Empire east of Los Angeles. Similar to our tour of the San Francisco Peninsula showcasing the San Andreas, this tour passes through a populated area and reveals how homes are built next to and on top of the fault zone. Although it’s possible to see many fault features in this tour, such as sag ponds and fault scarps, many have been erased by land development.

Length

Attractions

- Fault features

- Homes built on San Andreas

Difficulty

- Easy

- See Places We Visit

Elevation Gain

For those that have watched the virtual video tour above, reading this blog post will give you more insight into this segment of the San Andreas Fault. It also explains the touring route as well as more details about each stop that we’ll visit.

See the Trip Map for an interactive map of our touring route and a link to download the GPX file we created containing the waypoints for plotting onto Gaia GPS the places we visit. Using Gaia GPS’s Bedrock Geology layer plots the path of the San Andreas, making it easy to find many of the features described in this tour.

Fault Terminology

Throughout this tour, we’ll be visiting places where we can see signs of the San Andreas Fault. Those “signs” are what we call “fault features”. Here are some of those features explained.

Keep in mind that the San Andreas isn’t just a regular fault like many others, it is a significantly large fault. It’s actually a plate boundary – the boundary between the North American Plate and the Pacific Plate. Both of these plates are experiencing what’s called continental drift and are literally sliding past (or rubbing against) each other very, very slowly. This edge or division between the two plates is the San Andreas Fault. Earthquakes occur when that sliding turns into a sudden jerk of movement. Explaining further involves a lengthy discussion of plate tectonics, which is out of scope of this article. Learn more by Googling “plate tectonics”.

The San Andreas is also a type of fault known as a right-lateral strike-slip fault. That means, if you are standing on one side of the fault and looking towards the other side, the land on the other side of the fault would be moving to the right. That means, the land on the Pacific Plate, which would include the Los Angeles area, is moving northwest. The land on the North American Plate, including the San Bernardino Mountains and Mojave Desert to the north, is either stationary or moving very slowly to the southeast.

The fault isn’t always a single line or deep “crack” in the ground dividing the two plates. It can also be a “fault zone”. This zone can be anywhere from a hundred feet thick to a half mile across. These zones consist of many factures that are all related to each other. In some places on our tour, the fault is not more than 50 feet wide. In other places, it’s just under a quarter of a mile wide.

Here are some of the fault features we’ll see in this tour:

- Fault scarp: an abrupt and straight edge, like a step in the contour of the land

- Shutter ridge: a straight and shallow trough in the ground

- Sag pond: a low depression where water is trapped by the fault’s impermeable barrier of crushed earth material and begins ponding

- Linear valley: a long and skinny valley created by a significant strike-slip fault like the San Andreas – on this tour, we’ll constantly be looking at Lone Pine Valley for reference, which is a linear valley

Both scarps and shutter ridges were either created during an earthquake event or by slow movement along the fault, known as fault creep. Some scarps were created during earthquakes that occurred a few hundred years ago and still look like an abrupt step in the landscape. Other scarps are from earthquakes possibly thousands of years ago and are difficult to make out because natural erosion is slowly erasing them.

The challenge on this particular tour, which passes through a lot of developed land, will be to find those features. A lot of land was bulldozed and leveled to make way for development, which erased some of these fault features. However, in the first half of the tour, the fault passes over undeveloped mountains, revealing a lot of features. The second part of the tour passes through developed areas and features can only be seen in certain areas.

Trip Route

Our tour of this segment of the San Andreas Fault begins in the quaint town of Oak Glen and ends in the small community of Devore at the foot of the Cajon Pass. Since the fault hugs the southern edge or base of the San Bernardino Mountains, our touring route will essentially follow this edge. After starting in Oak Glen, we’ll pass through the towns of Yucaipa, Highland and San Bernardino, then ending in Devore.

Unlike most of our other tours that follow a route of one to five roads, this tour will be difficult to follow as it wonders down many different streets making many turns. For that reason, rather than provide left and right directions like we do on our other tours, with this tour, we’ll provide a list of addresses or placenames that you can navigate to, using your favorite navigation app like Google Maps.

Oak Glen & Yucaipa

Beginning in Oak Glen at the intersection of Oak Glen Road and Glen Road, we’ll begin heading west or downhill. For the next 2-3 miles, the road will zig-zag and pass within a hundred feet of the fault and, a few times, the road crosses it. Here, the fault will be on the right (the mountain side) and, in some places, be just behind buildings.

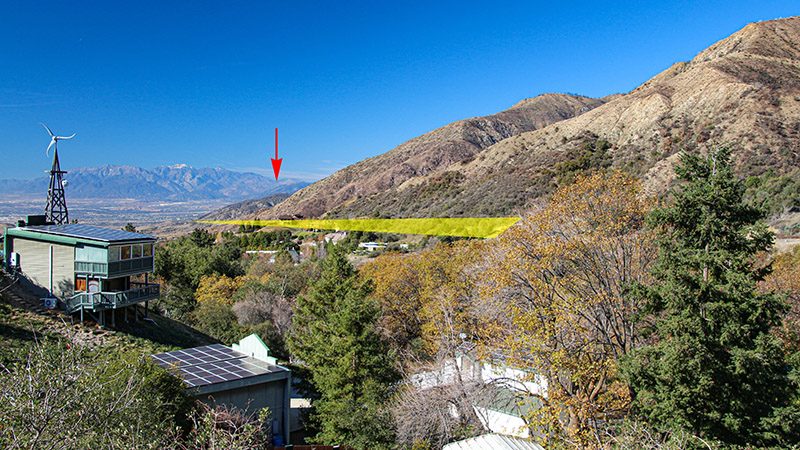

From here, way in the distance, we can see where our tour ends in Devore and, just behind Devore, we can easily spot Lone Pine Canyon, which is a linear valley next to the Cajon Pass. This is where our other San Andreas tour starts that passes through Wrightwood and over the San Gabriel Mountains. Lone Pine Canyon is about 40 miles away from here.

We’ll continue on Oak Glen Road down into Yucaipa and turn right (north) onto Bryant Street. We’ll head up Yucaipa Ridge Road to view both a sag pond and a shutter ridge that sit on top of the fault. From this point, we’ll also get a view of the fault and where we came from in Oak Glen.

Take note that in late September 2022, heavy rains caused a series of large mudslides that damaged many of the homes and businesses along this stretch of Oak Glen Road. The road was actually closed for two months after the mudslides. Fires from the previous years burned vegetation that keep soils in place. Without the vegetation, rushing water will easily pickup and carry topsoil and ash down the steep slopes, which is a common theme all along this tour from Oak Glen to Devore. The communities of Devore and Highland have also suffered from massive mud and landslides following large rainstorms months or years after wildfires scared the mountains above.

The steep topography of the mountains, coupled with the adjacent gradual slopes where these communities were built, is a product of the San Andreas Fault itself. Evidence of past erosion shows that mudslides and floods from the steep mountainsides above have been occurring all along this tour route for centuries. Not only are these mudslides the fault of a deluging downpour, it’s also the San Andreas’ fault (pun intended) for creating these steep slopes.

Hwy 38 & Mill Creek

Next, we’ll head up Hwy 38 a short distance to where the fault crosses the road, as well as the large drainage of Mill Creek. There’s little trace of the fault here other than possibly a few shutter ridges. Any trace of the fault was covered by the massive amounts of alluvium (boulders and gravel) that have flowed out of the canyon.

We’ll now head down (west) Hwy 38 as we travel away from the fault. After a few miles, we turn right onto Garnet Street, which turns into Greenspot Road. In the distance, we’ll see the massive Seven Oaks Dam. When we pan our eyes to the left, we’ll see a long stretch of the fault along the base of the mountains all the way to Lone Pine Canyon, which is now about 25 “crow fly” miles away.

Along this stretch of road, similar to what we saw along Hwy 38 a short distance back, we’ll cross over a large alluvial plain. This is a larger field of alluvium that has flowed out of the San Bernardino Mountains for a very long period of time. It has covered up any trace of the fault here, so no fault features will be visible here.

Greenspot Bridge & Seven Oaks Dam

Just before the road crosses the Santa Ana River, there will be a parking area and trailhead on the right. Park here and walk towards the dam on the paved bicycle path. This trail will take you over the historic Greenspot Bridge.

Built in 1912, the Greenspot Bridge actually began its life in Victorville, in the Mojave Desert 30 miles north of here, to span the Mojave River. When a wider bridge was needed, this bridge was moved and installed here in 1933. When traveling this road up until recently, this is the bridge you drove over and hoped there was no wide vehicle coming from the other direction! The name, Greenspot, came from an old hotel that was in Victorville. The newer bridge, that the main road uses, was built in 2015. As you walk over the bridge, be sure to read the numerous kiosk signs located around the bridge. However, none of the kiosks mention that you are standing on top of the infamous San Andreas Fault.

In this area where the bridge sits on top of the fault zone, one might wonder why a large dam was built here? Plus, the dam was built just recently (late 1990s). Seven Oaks Dam, which is one of the largest earth-filled dams in the USA, is designed specifically to withstand shocks from the nearby San Andreas. The dam is so thick that it would be impossible to cause it to fracture. Compared to Hoover Dam, which is tall, skinny, and composed of concrete, could fracture and fail if it were hit with a 8.0 magnitude earthquake.

More…

Pictures

Below are some pictures of what you will see along the way.

Highland

We continue west on Greenspot Road into Highland. The fault can be seen on the right, hugging the base of the mountains behind the neighborhoods. In one of the neighborhoods, a small park or greenspace is situated against the mountains and was built on top of the fault. Across Highland and San Bernardino, after city managers and developers realized homes were being built on top of the fault before the 1980s, land on top of the fault became off-limits to build on. To use up that space, parks or greenspaces were established.

That park can be found where San Benito Street turns into (corner of) Mc Lean Street. The long skinny park sits on top of the fault and is oriented in the direction of the fault that we’ve been following since Oak Glen.

We’ll then head up to Base Line Street, which is a main thoroughfare through Highland and San Bernadino. First, we’ll head to where it dead-ends by turning right from Greenspot Road onto Weaver Street, then right onto Base Line. In a short distance, the street passes by the base of the mountains on the left, which is where the fault sits. At Base Line’s dead-end, we can see the fault coming from where we just were at Seven Oaks Dam.

On Base Line, you’ll pass by the Natural Parkland Trailhead. The kiosks here talk about what to see in this nature preserve but does not mention the fault.

Just to the west of the trailhead along Base Line, topo maps show another sag pond. You can make out where it was (or is located during a wet year) by a large cluster of trees and a few palm trees near the intersection of Base Line and Alpin Street.

Heading west on Base Line, when we return to Weaver Street, we’ll turn right. This road turns into Highland Avenue, another main thoroughfare. After the road slowly turns to the west, turn left onto Cloverhill Drive. On the left, we’ll look at East Highland Reservoir, which is a converted sag pond and situated right on top of the fault. The sag pond is located inside a private club.

Continuing west on Highland Avenue, we cross over the 330 Freeway that climbs the mountains up to Big Bear and, just after the intersection, we’ll encounter a shopping center with Walmart being the anchor store. Unlike other shopping centers, the front face of the anchor store is not parallel to the street. Instead, it is angled about 15 degrees away from the street on its left side. Why is that? When you look at aerial imagery from a map, it is obvious – the angle is oriented to the San Andreas. Walmart sits directly on top of the fault. Taking a short drive around the backside of Walmart, the berm on the building’s north side is most likely a scarp but has been accentuated by terracing above it for the neighboring mobile home park.

Back to heading west on Base Line, turn right onto Orange Street. This leads us to an interesting loop road taking us through a small neighborhood built on top of the fault. It also offers a great view of the area around us including our next stop, the Yaamava’ Resort & Casino, formally known as San Manual.

The casino buildings were built on the south edge of the fault. Navigating to Piedmont Drive and Willow Drive will give you an overall view of the fault and its relationship to the casino property. The steep sloops on the north side of the property, is the fault. Then, we’ll head up Willow Drive to see more houses built on and next to the fault. In fact, most of Willow Drive is directly on top of the fault line plotted on the geologic map.

San Bernardino

From Highland, we’re going to make a big jump in distance to the northwest side of San Bernardino, to the campus of Cal State University San Bernardino. In between here and Highland, the fault continues to pass through many neighborhoods, including more parks like the one we saw earlier built on top of the fault.

We’ll navigate to Devils Canyon Road and Campus Parkway, then continue driving north up Devils Canyon towards the mountains. In the distance, we can see a set of large pipes coming down the mountainside. This is the California Aqueduct. It transports water all the way from Northern California. On the other side of the pipes is a large storage reservoir named Lake Silverwood. The buildings at the bottom of the pipes include a powerhouse that generates electricity to energize the pumps that carry the water through the aqueduct’s long length. Obviously, the aqueduct is a significant water source for the Inland Empire region.

Just before reaching the aqueduct facilities on Devils Canyon Road, both the San Andreas and another fault, named the Mill Creek Fault, cross the road and the aqueduct, which are the large above-ground pipes you’ll see on the left. The San Andreas crosses the street just before a grove of large eucalyptus trees, and the Mill Creek crosses it just after the trees.

One of course would wonder how well the aqueduct and these facilities would survive when a large earthquake on either of these faults will occur. We couldn’t find many details on what types of precautions engineers took to protect these facilities from violent shaking like the extra precautions taken at Seven Oaks Dam. The aqueduct was built in the 1960s and it wasn’t until around 1970 when geologists understood the significance of the San Andreas (of it being a plate boundary rather than an ordinary fault). One would hope that retrofits have been on-going that would protect vulnerable equipment from the shaking that will occur during the next earthquake.

Devore

Our next stop is the rural mountainside community of Devore, also known as a junction of two freeways leaving the Los Angeles area – Interstates 15 and 215. From Cal State S.B., we’re going to jump on the 215 Freeway, head north, exit at Devore Road, then turn right.

Just before exiting the freeway, looking to the right at the base of the mountains. You’ll see a few long abrupt ridges that look like fault scarps. These are easily mistaken for fault scarps along the San Andreas, but they are not. These are ridges that were cut into the landscape from erosion and violent floods that have come down from the adjacent steep mountainsides. The fault is located closer to the base of the mountains.

We’ll take the steep course of Devore Road north towards the mountains and continue north as it seems the main road turns to the left (west), which becomes Kenwood Street. Staying on Devore Road, it will soon turn right and turn into Foothill Street. After a few hundred feet, the fault runs parallel the road on the left. Further down, the road cuts through a ridge that was pushed up by the fault.

Turning right onto the next street, which is Knoll Street, we pass through a shallow dip or depression. Similar to when we visited East Highland Reservoir on Cloverhill Drive, a depression like this often marks where a strike-slip fault crosses a roadway. Several examples of such depressions can be found all around Devore. In fact, when we continue on Knoll Street for another few hundred feet, it crosses a second depression. This is the Tokay Hill Fault, named after nearby Tokay Hill. This fault is only a mile in length. Devore is actually riddled with a lot of shorter faults because of its proximity to the convergence between the San Bernardino and San Gabriel Mountains.

Tour’s End

This concludes our touring route of the San Andreas Fault between Oak Glen and Devore. While high up in Devore, as you drive around the streets, be on the lookout for traces of the fault alongside the base of the mountains – where the semi-steep neighborhoods of Devore transition to the very steep edge of the San Bernardino Mountains.

Seeing the sights between Oak Glen and Devore will certainly take up a good part of the day. To spend another day touring the San Andreas, you can pickup the beginning of our San Andreas Fault tour near Wrightwood, which begins a few miles north up Route 66 from Devore.

What We Found Interesting

When we went on this tour to investigate the details and photograph the places you’ll see, there were several things that we found interesting, maybe even odd.

In general, we were amazed that there were no signs or kiosks pointing out the location of the San Andreas anywhere along our tour route. Where roads crossed the fault and it was easy to see it, in order to gain more public awareness, it would be helpful to place signs indicating where roads cross the fault. Along with the kiosk signs that we read along the tour explaining the surrounding nature, it would be easy to add a paragraph, or even a separate sign, that explains how the surrounding landscape has been affected by the San Andreas.

In other places in California, such as near Paso Robles and in the Bay Area, signs have been installed indicating that you are crossing the fault or simply looking at its trace. Installing some signs such as these may be helpful in educating people living with the fault in the Inland Empire region.

When we encountered and talked to three different people during our drive, we were surprised that they were not aware that they were standing very near the fault. Naturally, we don’t expect the common person to know the location of the fault. The science of geology behind fault systems like the San Andreas is complex. However, certainly in Florida, residents there understand how weather systems take shape and run its course. It’s surprising that in the Inland Empire area, people don’t seem concerned or aware of the various faults. That will probably change when the next large earthquake hits this region.

When living near the region (Victor Valley) for many years and attending various geology classes, it has come to our attention that two significant earthquakes occurred on the San Andreas somewhere near Wrightwood in 1812 that would have impacted the area this tour covers. Called the Capistrano or Wrightwood earthquake, it shook a large area of Southern California. The only known deaths were 40 Native Americans attending mass at Mission San Juan Capistrano, which was poorly constructed. Since the area was barely populated then, there were no accounts of the quake, other than the occupants of the missions. Geologists studying this portion of the San Andreas agree that the event most likely occurred on it or the nearby San Jacinto fault. The magnitude was estimated to be between 6.9 and 7.5.

With the 1812 quakes in mind, no other known event occurred on the San Andreas from Wrightwood, down to the Coachella Valley (Palm Springs). The age-old question still exists quandary still exists, on average, how often does an earthquake occur on the San Andreas at different places? This is a question that geologists are having a hard time answering.

The Places We Visit

This section lists the places we visited and mentioned in the tour description above, as well as the various fault features you can find. If you use a navigation app like Google Maps, you should be able to key these intersections, addresses and placenames into the app, and it will navigate you to each of the places.

Along with the places to navigate below, it is very helpful to use the Gaia GPS app, along with the downloadable GPX file we provide below, to locate these places, along with where the San Andreas Fault and zone is located using the app’s Bedrock Geology layer.

This list of places is available for PDF download below. Once the PDF is loaded on your phone, you can open it, then “tap and hold” to select the placenames or addresses, copy them to the clipboard, switch to a mapping app, then paste them into the search box of the mapping app. Using this method, you can quickly and easily navigate to each of the places.

Oak Glen Rd & Glen Rd, Oak Glen – the beginning of our tour – head west or downhill

38392 Oak Glen Rd, Oak Glen – Apple Blossom Ranch; fault is behind these buildings

0.3 mile down Oak Glen Rd – large turnout on the right; offers a great view of the San Andreas Fault to the northwest to Lone Pine Canyon (Cajon Pass) 40 miles “crow fly” away

38490 Oak Glen Rd, Yucaipa – fault is behind the Oak Glen Steak House

0.6 mile past Steak House – fault can be seen on the right as a straight line where the gradual slope turns to a steep mountainside

Yucaipa Ridge Rd & Quartz St, Yucaipa – head up this steep road to view both a sag pond and well-defined shutter ridge

0.7 mile from Bryant St & Hwy 38 – turn around at the large turnout on the left (west); this is where the San Andreas Fault crosses the road and the Mill Creek drainage

Old Greenspot Bridge – trailhead for walking up to the old bridge and examine the area and kiosks – the top of Seven Oaks Dam can be seen up the canyon

San Benito St & Mc Lean St, Highland – long skinny park or greenspace situated on top of the fault

Base Line St & Brookwood Lane, Highland – Natural Parkland Trailhead; road is next to the fault on the mountain side; Base Line will dead-end with a view of the fault heading back towards Seven Oaks Dam

Base Line St & Aplin St – sag pond just north of this intersection

Highland Ave & Pleasant View Ln – fault crosses diagonally over this intersection; notice the skinny long “no-man’s land” that exists between the rows of homes on both sides of the road

6892 Cloverhill Dr, Highland – just beyond the Spring Lake Clubhouse, on the left is the East Highland Reservoir, a sag pond located on the fault

4210 Highland Ave, Highland – Walmart just past the 330 Freeway; building is oriented in the direction of the fault; Walmart sits directly on top of the fault

3435 Holly Cir Dr, Highland – loop road going through small neighborhood next to fault with great views of valley below

Yaamava’ Resort & Casino – fault is located directly behind casino buildings on Piedmont Drive

Willow Dr & Hemlock Dr, San Bernardino – street and houses located directly on the fault

Hill Dr & Acacia Ave, San Bernardino – Newberry Memorial Park is another greenspace located on the fault

Devils Canyon Rd & Campus Pkwy, San Bernardino – pass by Cal State San Bernardino campus and head up Devils Canyon to view California Aqueduct facilities; faults are located near grove of eucalyptus trees

Dement St & Cable Canyon Rd, San Bernardino – looking up Cable Canyon Rd, long abrupt ridges that look like fault scarps are not; fault is at base of mountains

Knoll St & Foothill St – head south on Knoll Street to see the two depressions the street passes through, the first being the San Andreas Fault and the second the Tokay Hill Fault

Swarthout Canyon Rd & Cajon Blvd – beginning of our San Andreas Fault tour near Wrightwood

Click here to download a PDF file of this list of places along the tour. Remember to copy/paste these placenames and addresses from the PDF onto the search box of your navigation app (e.g., Google Maps).

Trip Map

To help plan your trip, either use our interactive Google Map below or download our GPX file that points out the places to see that are mentioned in this chapter.

Click here to download our GPX file that follows our tour of the San Andreas Fault through San Bernardino. We recommend using a GPS mapping app, such as Gaia GPS, to view these points on your computer or to locate them using GPS with your mobile device or phone. Click the ad below to purchase Gaia GPS using our discount code which offers up to a 50% discount.

Learn more about our maps.

Comments

Read and leave comments about this post on YouTube.

Support Us

Help us fill up our tank with gas for our next trip by donating $5 and we’ll bring you back more quality virtual tours of our trips!

Your credit card payment is safe and easy using PayPal. Click the [Donate] button to get started: